The typical nature of a Hong zoom is provocative, with each inspection resulting in a separate personal narrative. In the following shots, a distrust of relatives drives our characters, if not into another country, at least into another place temporarily until the scandalous uncle has turned himself in; hinting slightly at a case similar to Hong’s own Night and Day (2008). If not entirely true, it can be said that all of Hong’s characters share a polymorphic existence across the same universe, living time and again; sometimes as free-spirited women who are foreign to the way of cinema’s scale and sometimes as married directors who frequent showers of unrequited love and desert affection for flings of cyclic infidelity. Although the description might be one-note, his films are not. Shortly after the completion of his film, In Another Country (2012), Hong was given total freedom by the production to make a short with a third of the same cast.

The typical nature of a Hong zoom is provocative, with each inspection resulting in a separate personal narrative. In the following shots, a distrust of relatives drives our characters, if not into another country, at least into another place temporarily until the scandalous uncle has turned himself in; hinting slightly at a case similar to Hong’s own Night and Day (2008). If not entirely true, it can be said that all of Hong’s characters share a polymorphic existence across the same universe, living time and again; sometimes as free-spirited women who are foreign to the way of cinema’s scale and sometimes as married directors who frequent showers of unrequited love and desert affection for flings of cyclic infidelity. Although the description might be one-note, his films are not. Shortly after the completion of his film, In Another Country (2012), Hong was given total freedom by the production to make a short with a third of the same cast.

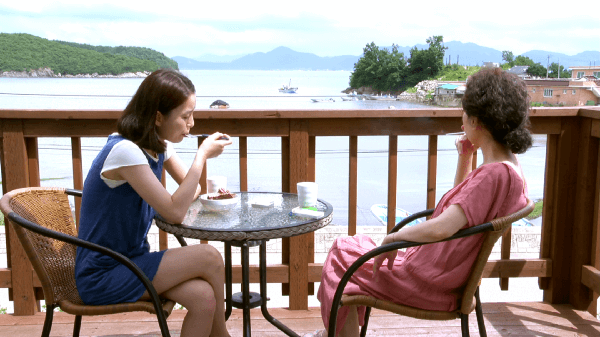

Somewhat vaguely, the beginning feels similar to In Another Country as Jung Yu-mi’s character (Mihye) compiles a list of things she wants to occupy herself with during this temporary trip instead of recounting her experience into a screenplay trisected by thematic variance. In the next shot, the list is superimposed on the landscape and after a few lingering moments, the narrative shifts to her mother expression her worry about Mihye’s marriage and finding a partner. Soon they meet Yoo Jun-sang, a director whose recently released film was considered a national success. A rhythmic use of focus and witty conversation suggests the space between these people is formed of assumptions. Mihye and her mother imagine the director’s life to be starlit, happiness aplenty but Hong rejects this imagined elevation by a simple game of badminton where both characters are equally affected by wind but nonetheless enjoy the game and company; cinema out of context being vulnerable to the context of its circumstance.

The director and Mihye connect in the events of a loose date accompanied by her mother. Now he is recognized for his modesty and kindness, and her beauty is appreciated as special. The two hold hands in an attempt to digest the other’s intricacies. Mihye confides in him that she is scared of her mother. The director promises to take her away first thing in the morning. Slowly this unusual proposition from a Hong film stands out, drifting away from a constructed emotional semblance. As the shot lingers for a few moments of them looking at each other lovingly, I’m reminded of The Turning Gate, the aspect ratio wordplay in Virgin, the remaining fish in Kangwon Province, and perhaps the materializing fact that love is a fantasy of other people, of other films where the creator is not as critically honest of their human shortcomings. Hong’s notion of love is a far-fetched dream whose existence is limited to the plane assembled by the nuances of creative thought and the gentle touches of a paper and pen.